Earlier this year a friend sent me an article in Hudson Valley magazine about how scientists had discovered a 385-million-year-old forest in Cairo, New York. I remember thinking to myself, Wait, we have trees that old? How big are they?! Do they look like normal trees?

Then I read the article and realized they are actually fossils of trees.

But still, that sounded really cool, and I wanted to go see this mind-bendingly old forest. The problem was, the area where it was discovered is an active archaeological site and not open to the public.

Fast forward a few months and I randomly got a call from Nhi Mundy, the editor of DV EIGHT Magazine, asking me if I wanted to photograph Charles Van Straeten, the scientist who had discovered the forest, at the site.

Absolutely.

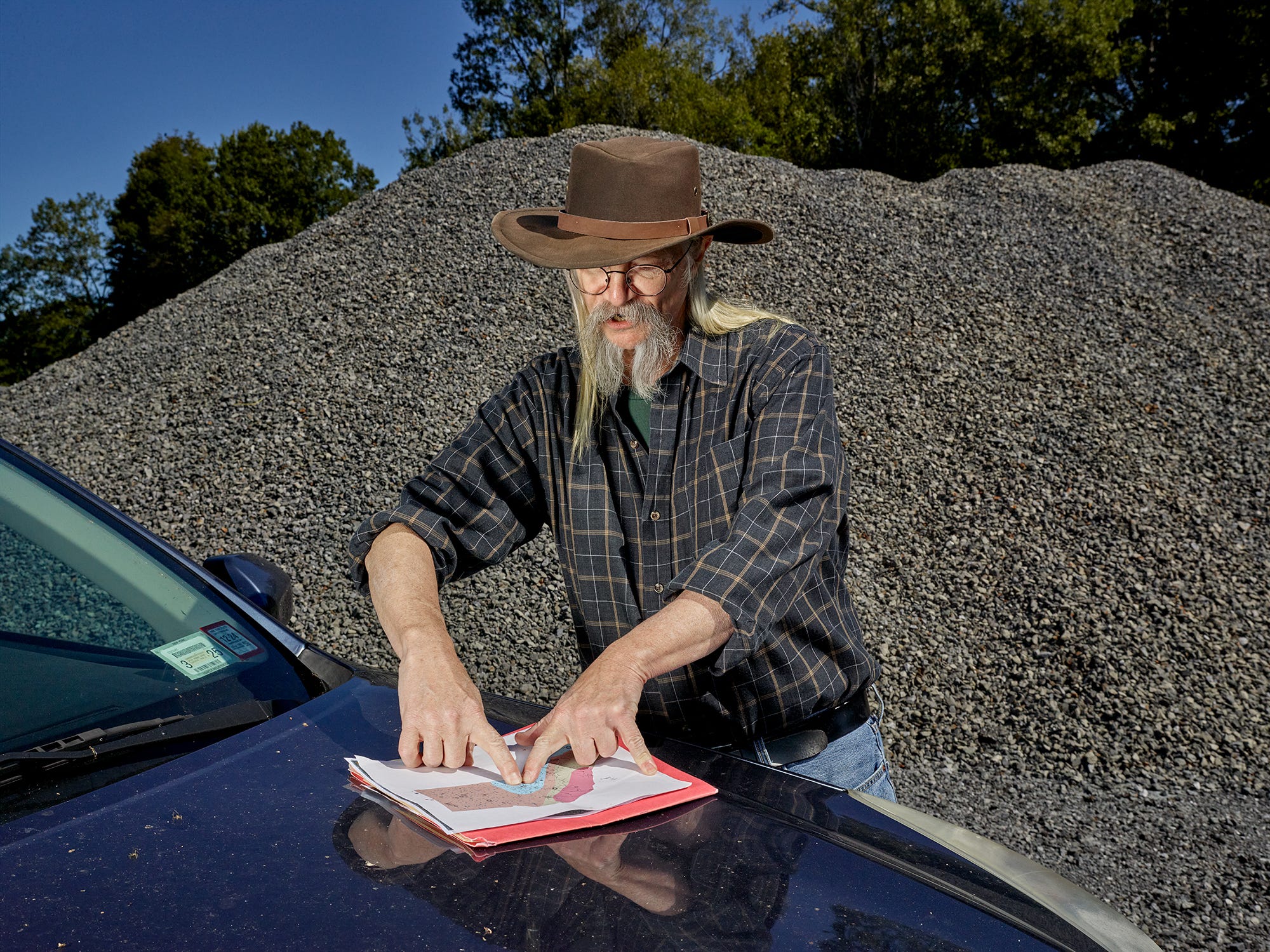

So on a beautiful early September morning I drove two hours north and met Chuck at a nondescript municipal lot in the town of Cairo and followed him to the site, which is in an old quarry. There was not a cloud in the sky. High sun. Long shadows. Exactly how I like it!

I made a series of photographs with him over the course of an hour while he explained to my assistant and me what we were actually looking at. It was truly fascinating! Root systems. Geological processes. Evolution. Our complete and utter insignificance!

This newsletter is an edit of those photographs, along with the full article by Eddie Brannan as it appears in issue 19 of DV EIGHT Magazine, which you can find for free at various shops and cafes around the Catskills.

While you and I might have trouble recalling last week, Dr. Charles Van Straeten—who prefers to be called Chuck—studies events that occurred hundreds of millions of years ago.

Van Straeten is a paleobotanist at the New York State Museum, and in 2018, he and his team made a remarkable discovery right here in our region: a 385-million-year-old forest, the oldest in the world. Fossils of the forest's root system were uncovered at the bottom of a disused quarry in Cairo, NY, and predated the previously oldest known tree fossils, found in Gilboa, NY, by about five million years.

Consider that the human species has been around for only 300,000 years. Van Straeten can grasp time on that scale. He credits it as part of the big drive that got him into geology and paleontology in his 20s. Initially, Van Straeten came upstate to attend an avant-garde music school, playing trombone. Then, at thirty, he went back to school to study botany. Two years earlier, he had heard about an opening for a curator of sedimentary rocks at the New York State Museum and thought, "That would be a cool job." In 2000, he took the position and still holds it today,

Beyond his groundbreaking discoveries, Van Straeten shared a compelling portrait of the ancient world, revealing the grandeur of trees so old they defy comprehension.

First things first, I have to admit I find it hard to grasp numbers as big as 385 million years, the era in which these trees and forests lived. They're just such big numbers, such a huge amount of time. How do you manage to rationalize it?

Oh, that was a part of the big drive that got me into geology and paleontology in my 20s. Just the wow factor thinking about times at those scales. My grandmother was born in 1888 and she might have been in her mid to late 20s before she saw her first car in rural Iowa, so that's a long time if we think about our individual lives.

If we think about written history, the Chinese invented a system of writing 5,000 years ago.

But still that's nothing. Here in Albany, New York, there was a mile of ice over the top of the land 24,000 years ago. Hominids emerged six or seven million years ago and humans one million or less. We just need to keep looking further back until we arrive at the Devonian period roughly 420 to 360 million years ago.

When we talk about the world in the Devonian period, we're talking about a completely different planet, geologically speaking, right? Could you tell me a little bit more about what the world was like 385 million years ago?

During the Devonian period, where we are now was close to 30 degrees south latitude, south of the equator, and tropical. It was much hotter, much wetter. When we talk of these trees and the world in which they grew, we are talking about a time before the birds, before the invertebrates, long before the dinosaurs.

At that time, there were smaller continents colliding with Eastern North America that built up a mountain belt from East Greenland to Alabama and Georgia, including an Andes-scale mountain belt, right on the north east coast. At the time of the Cairo Fossil Forest, there was a shallow sea that extended from Eastern New York all the way out to west of the Mississippi.

Originally, the sea stretched as far as New England in the early part of the Devonian and it had been slowly filling in from the east. As the mountains started to build, so much mud and gravel was being pushed ahead of them that it was filling the sea in from one side. Land kept building westward, and that is where the Catskill Mountain forests are found today.

How do we know this? What does the geology of the region tell you?

When you look at the rock formations in the Catskills today, you can see that there are hard ledges of rock that stand out as overhangs. The hard rocks are river channel deposits. And then the colored rocks that are more muddy, like shale, were the floodplains of these rivers that were bringing all this sediment from the big mountains out into New York. It was on those floodplains where these early forests, the Cairo quarry and Gilboa quarry trees, lived.

Looking at that period from a geobotany perspective, why were the trees preserved in that particular place from that particular time?

Well, let me step back a little further. Actually, the Devonian period lasted about 60 million years. At the beginning of that period, your tallest plants were only the height of the tip of your thumb to the extended tip of your index finger. They didn't have leaves, but they had the green color of chlorophyll, which of course is what made their nutrients—photosynthesis.

Their branches were relatively soft and very short, not really branches yet. They were very rudimentary versions of what we would now consider a plant or a tree, very prototypical.

So they evolved into the trees we know now?

When I talk about some of the things that life has done over time, I no longer just say this is what evolved, but that they developed new technologies in order to allow them to move onto land. Because if a plant lives in a pond and the pond drains, it dies. So in order to go from living in the water to moving onto land, plants had to develop new technologies that would protect their outer covering so that the water didn't just evaporate right through. They also had to develop a rigid stem support so they could stand up. And they also had to develop a transport system to move water nutrients from the roots.

Why move onto land? There was almost nothing else living there already, so they had a whole new environment to live in. And out of the water, they'd get increased light from the sun for photosynthesis and they could take the CO2 out of the atmosphere more efficiently than out of the water.

Could you talk about the original 19th century discoveries at Gilboa?

So back in, I think it was 1856, someone in the northern part of the Catskills around Gilboa came across an odd rock in the sedimentary rocks up there. It was brought to Albany, which at the time was one of the main centers of geology and paleontology in North America, and it was examined by the geology and paleontology staff who figured out it was the interior of the lower part of a tree that was hollow all the way up. Kind of like a modern palm tree. Around 1910 they started collecting fossils from Gilboa.

They had found all these tree stumps in the past where the hollow interior of the trees had been filled with sand and preserved, but they started finding several other smaller plant fossils and so the Gilboa areas became globally known at that time for its Devonian fossil plants.

Let's move on to Cairo and your specific involvement in the discovery there.

Around the late 1950s to early 1960s, the Cairo quarry was dug out. They were taking out about 20 feet of layers of hard rock and hard sandstone because they were using it to build the interstate that goes from New York City up to Montreal. Paleobotanists started going there and found some plant fossils, you know, just the thin little branches and the smaller plants and a lot of other things as the new layers of rock were revealed. And it continued. In the 2000s there were still a couple people, especially from the State Museum, who were going out there and finding different fossils. The world's oldest known liverwort plants, these little single-leaf plants that are found around very damp areas such as waterfalls, came from Cairo in the early 2000s. They date from about 385 million years ago. So same as the trees, roughly. The layers are a little bit separated, but not much at all.

It seems that quarries have had a major effect on these particular discoveries.

Quarries are places where you get to see more of the rock than you would see on the sides of the Catskill Mountains. There's probably thousands and thousands of forests in the rocks in the Catskills. But it's so covered with thin soils and forest cover that you don't get to see into the rock, so Cairo had been a significant place for fossil plant discoveries since the large-scale quarrying in the late '50s.

So how did the actual discovery happen? What was the sequence of events?

I was out with two of my peers from the New York State Museum, Linda Hernick and Frank Mannoll. I was looking for different sites in the Catskills that I could take geologists and paleontologists in the fall for a field trip. Linda and Frank had been in that quarry a lot over the years, and that would be one of seven or eight different stops.

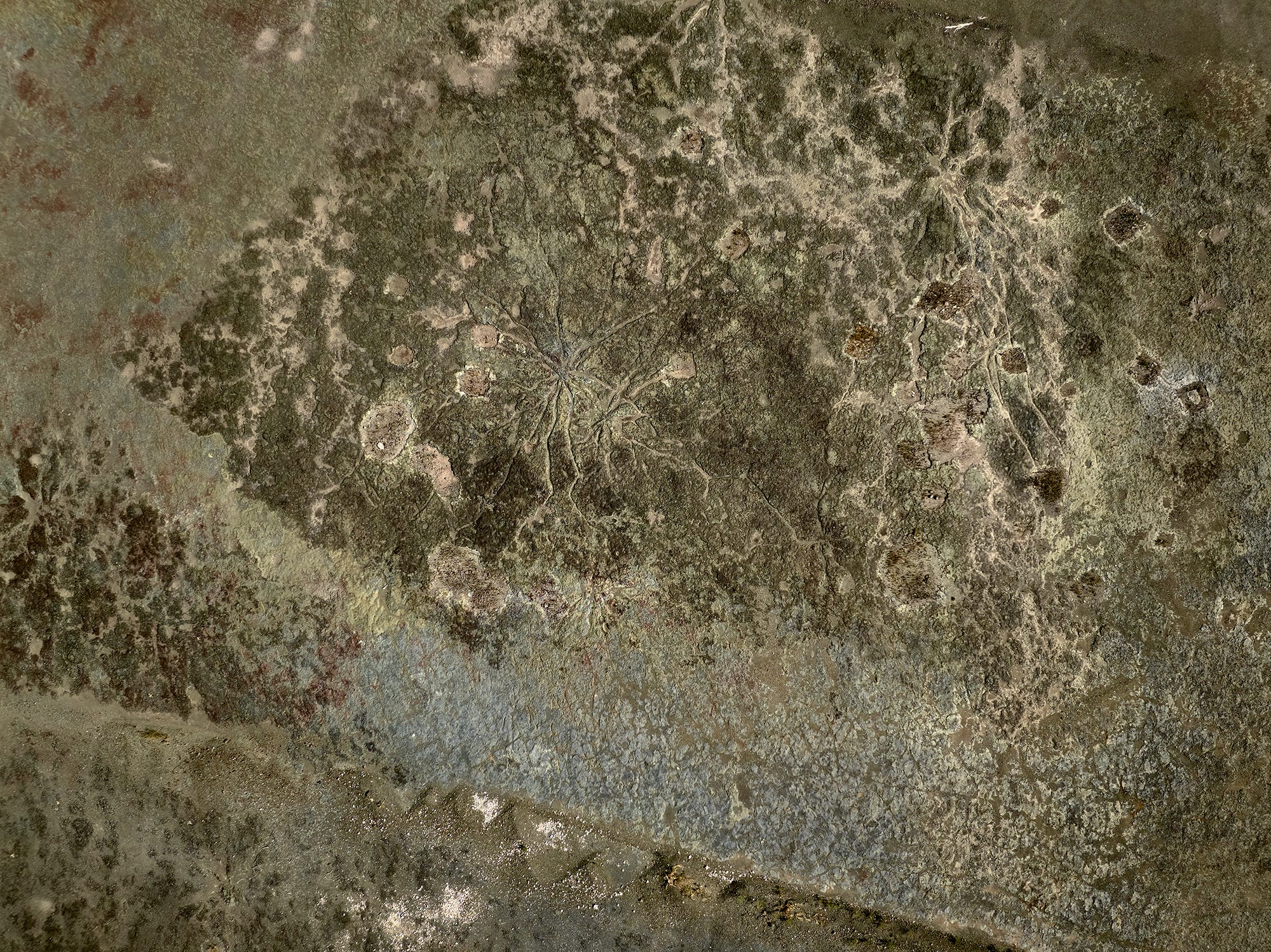

We looked at some things in the quarry and then at one point we were walking across the quarry floors and my eye unconsciously picked up a pattern. I wasn't even looking down, but I caught sight of a small part of a poorly-infilled runnel that looked like a little shallow gutter in the rocks on the floor.

You recognized its significance?

I had seen some things like that in Marine Walk in Western New York, when I was in grad school, and my unconscious mind had a search image already implanted, like an eye muscle memory.

When a hurricane comes along and it pushes water up onto the land, there's this tremendously powerful, rapid current of water that flows back out below the surface of the sea. That creates a lot of turbulence under the surface, and when it gets to the muddy areas of the seafloor it digs out these small gutter-like features. As the storm energy decreases, sand fills in those depressions.

Linda, Frank, and I started looking around and I was following one of these gutters. Frank found another, Linda found another, and we walked inward following them and they all met at one place. There were eleven major gutters that converged there and as we stood there it didn't take very long for us to realize, holy cats! These were roots and that's where a tree stood 385 million years ago.

What did that discovery feel like?

Oh, that was amazing to us. And we started looking around and we found more, more roots and root systems that came to meet in a single place where another tree stood. Some of the trees were big, especially that first one. Some of the root systems went out 24 feet.

So how tall do you think the tree itself would have been? Do you have any sense of that?

That I don't know. Maybe it's easier to talk about how far the tree reaches outward? Typically tree roots will go out as far as the branches extend, so a 24-foot root system suggests quite a large plant. And that was just in one direction. In the other direction, they'd be like that too. That means these were big trees.

What happened next after the discovery? What was the process of identifying what you found?

We just started looking around and we kept finding more and more. The quarry at that time still had a good amount of gravel over it so you couldn't see everything. We brought big brooms out and started just brushing surfaces off with them, then used little brooms to get down into the details. There were actually three different kinds of trees in the Cairo forest, like there had been in Gilboa. One of them was present in both places, but the other five were completely separate species, so it's quite a diverse forest.

How did you document what you found?

There were a number of old bricks in the forest. We started taking those bricks and setting them right where we found trees. Dr. Bill Stein [Associate Professor of Biological Sciences at the State University of New York at Binghamton] and Dr. Chris Berry [a palaeobotanist from Cardiff University in Wales] came to start mapping the site. Bill Stein said the first time he came and stood where a tree had stood in a Devonian forest about 385 million years ago was one of the most powerful moments of his life because for the first time, having studied fossil plants and trees for all these years, he could look around and see where the other trees stood in a Devonian forest.

Eventually, the group started mapping where all the trees were, putting out strings like they do, making rectangles so you can map a small area and then put them all together. Bill Stein built a type of camera stand 12 feet in the air and he would shoot each one of those rectangles, then stitch the photos—a couple hundred, certainly—together to create the first map. Later he started using drones, too.

Once they mapped it, how big was the forest?

It was the equivalent area of the goal line to the 70-yard line on a football field, but that's only what has been mapped so far. There's more in the quarry. A forest like that might have extended for many miles.

Tell me about how the discovery was received by the general public.

When the news came out at the end of 2019 it was in the news all over the world. Even this year it's caught a lot of attention. I've been giving public talks about the Devonian forests in the Catskills. I've had a lot of interviews this year and it surprises me, there's so much interest.

I think it takes me right back to what I was saying at the very beginning. Most people are kind of fascinated with the enormity of these numbers and the idea of being able to literally stand where a tree had stood in a forest 385 million years ago.

Yes, that was one of the things that just broke open my perspective. It's thinking about time the way geologists think about time.

Thank you to Nhi Mundy, Eddie Brannan and DVEIGHT for allowing me to republish this story.

Special thanks to Kristen Neufeld for sending me the article about this discovery and for assisting on the shoot.

Don’t forget to watch the Hotline Show.

ARE YOU SUBSCRIBED?

If not, hit that button below. This newsletter comes out once a week (maybe). The main stories will always be free but you can pay and if you send me your mailing address I will send you something special in the mail.

You can also support this newsletter by hitting the “like” button or sharing it with a friend.

Thank you.

"holy cats!" indeed!!

This was cool.