I’ve never liked filters.

I don’t mean the kind of photographic filter you put on your lens, like a haze, neutral density or a UV filter.

I mean the kind that you add to your photos to make them look like an old camera made them.

These days people might call the filter effect on their photos “color grading.” Some of this is okay if you are just looking to enhance a raw file, to help give the photo a color style that might reflect your current sensibilities while remaining mostly true to the time you exist in.

But in the early days of digital photography and of course those early Instagram days, there were preset filters you could apply to your pictures to make the photos you took look like they were taken with an old camera. Filters that looked like a Holga, a Polaroid, or some other toy-type camera and film combination to give the impression it was made with something other than a digital camera. You know what I’m talking about. They had that nostalgic feel and people liked them because it made their digital photographs look less digital, as if that was a bad thing.

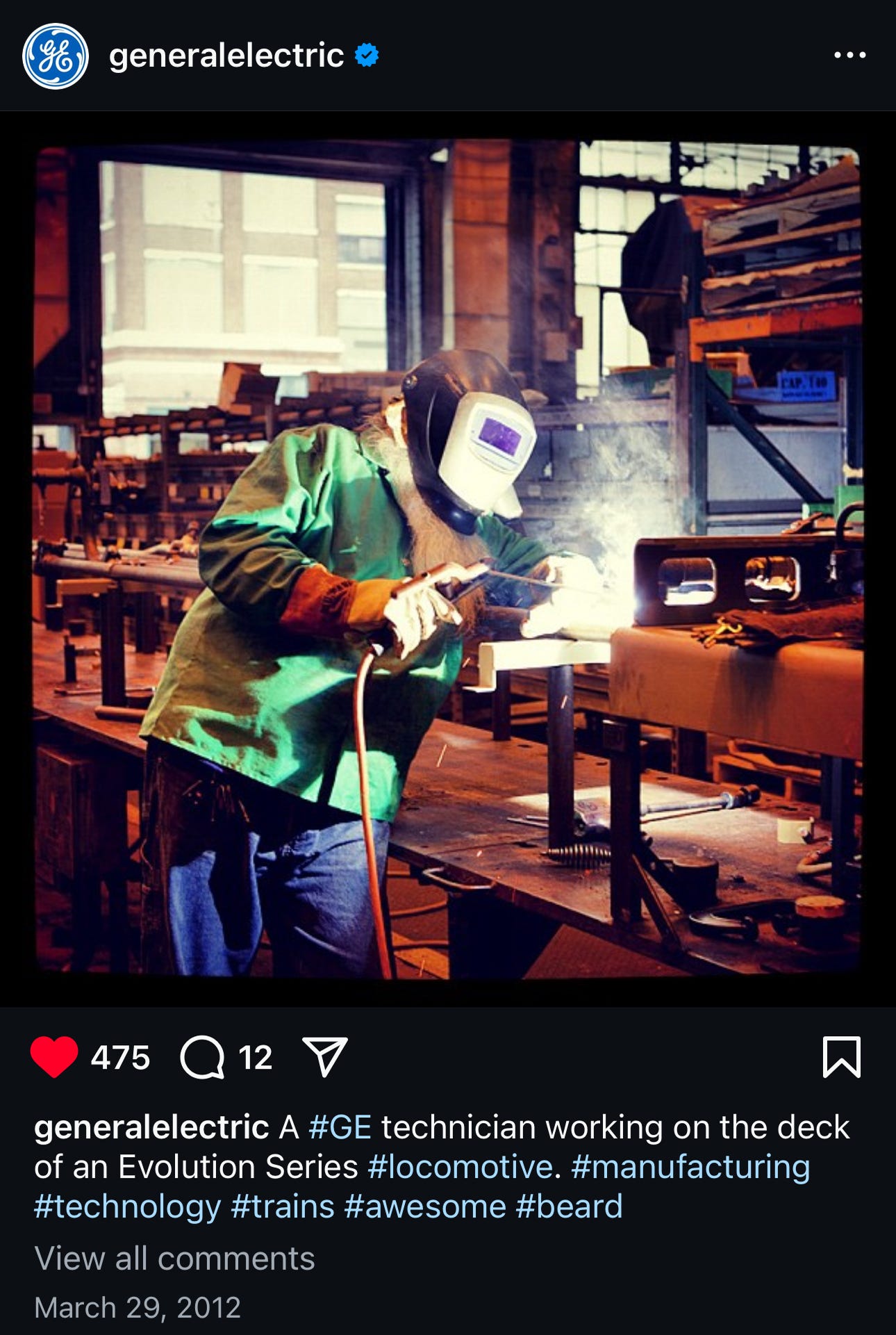

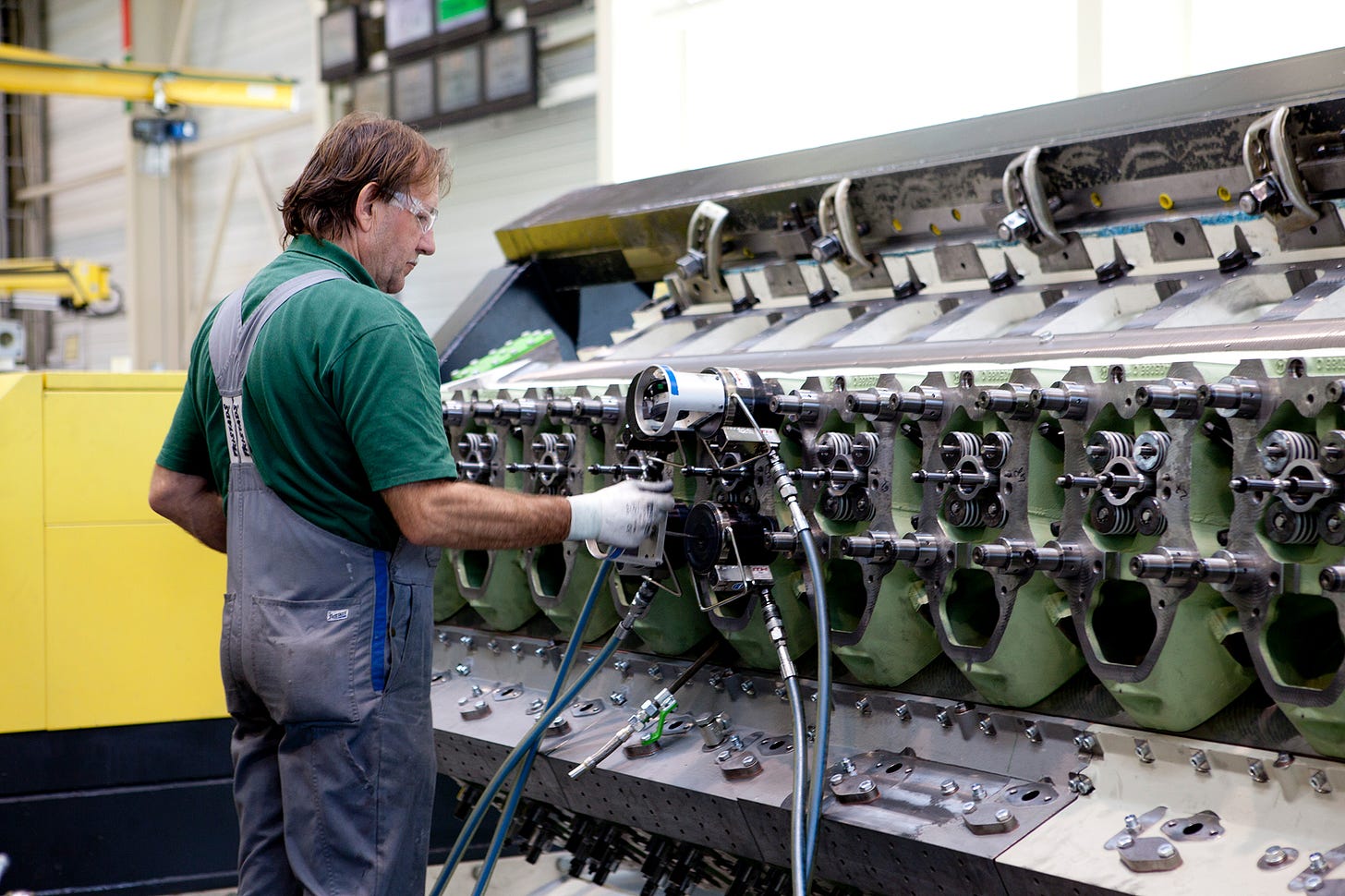

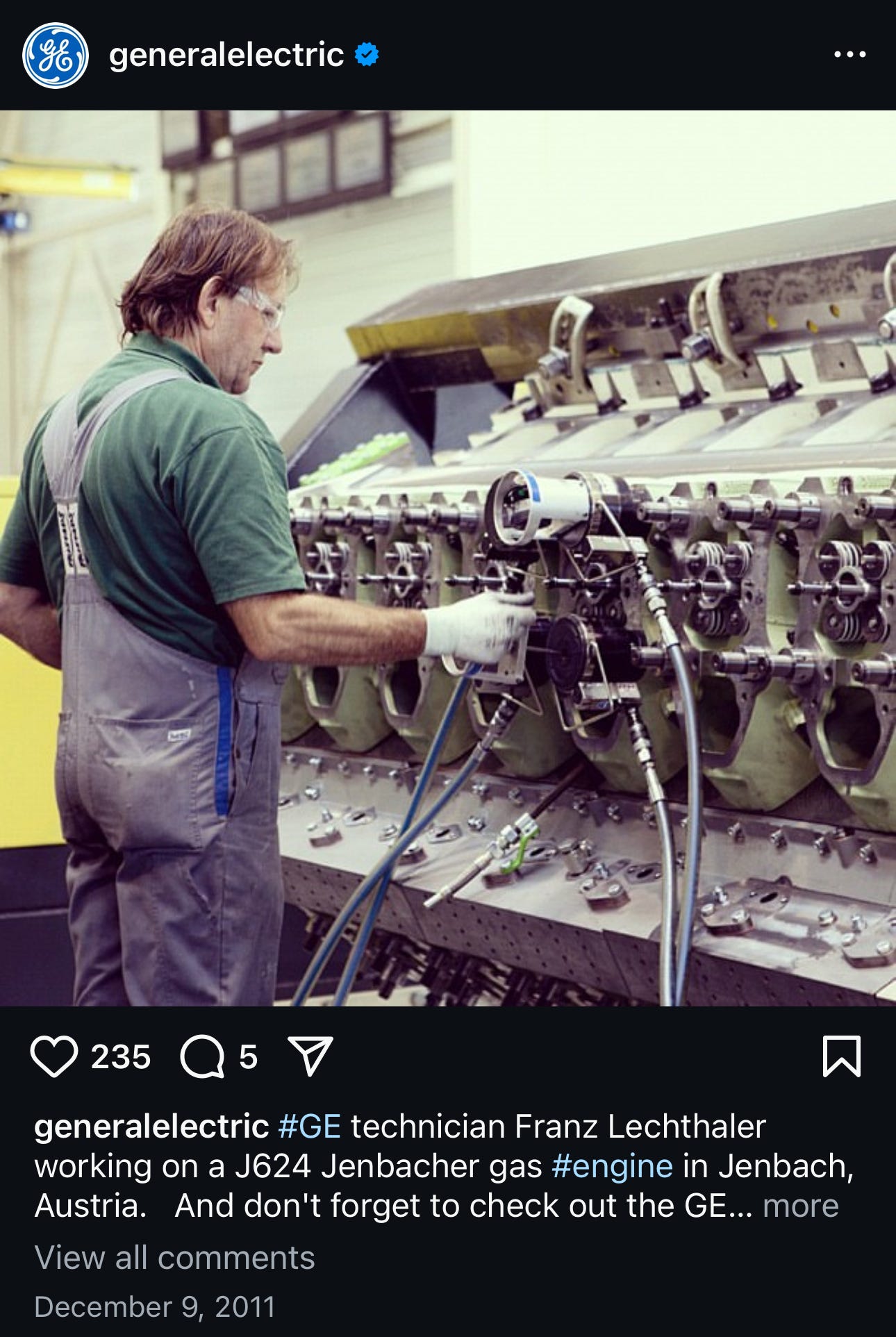

Back in 2011, I was hired by General Electric to photograph a number of their factories around the country and in Europe, specifically for their Instagram account.

I think some have said GE was one of the first major companies to embrace Instagram as a platform to promote their brand, and in a way I might be indirectly responsible for the acceptance of this type of online commercialization.

I apologize.

Anyway, when I made these pictures, I remember truly hating Instagram, despite the fact that it was going to be the end use for these photographs. I didn’t think “real photographers” would use such a platform. Looking at photos on a phone?! That was an affront to my pretentious art school beliefs. The only correct way to view photographs was in print or book form. Maybe, just maybe, it was acceptable on a nice calibrated computer screen if you knew what you were doing.

Nonetheless, I took the job because it seemed like an incredible opportunity to see amazing things. And of course, because it paid well and I am a giant sellout.

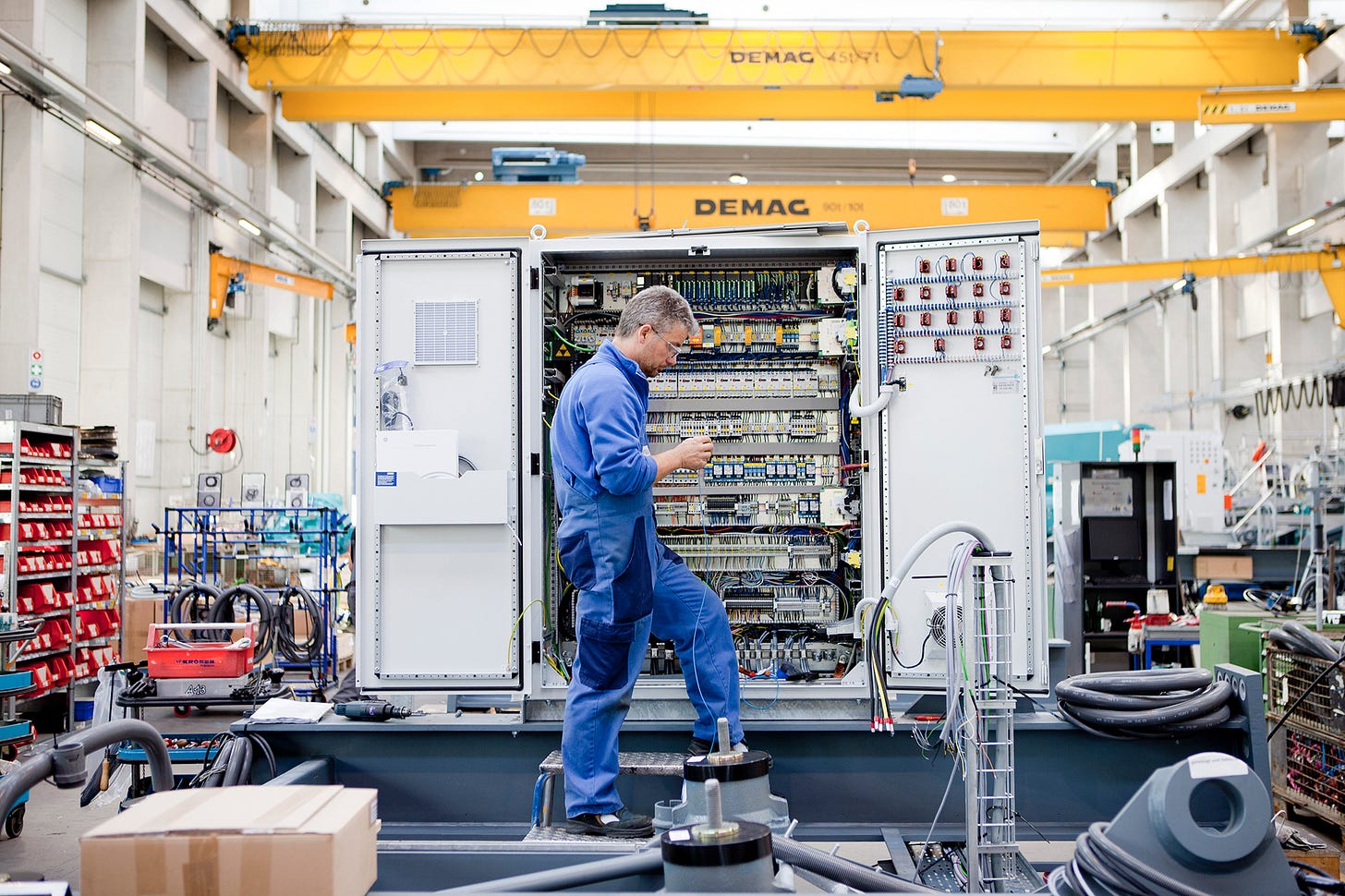

The job was truly spectacular and the places I went were fascinating. I was able to make amazing photos inside of factories that manufactured jet engines, locomotives, washing machines, windmills and more. It was a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity and I think I made some pretty cool work out of it.

At the end of each shoot, I would provide an edit of my photographs, mostly shot on a Canon 5D MarkII.

Then GE would add a filter to the photos and post them on Instagram.

This drove me nuts!

At the time, it was hard for me to articulate what it was that bothered me so much about it, and I didn’t think I was in any position to really challenge it anyway. So the photos I made got filtered and the pictures got posted. That was that.

But I never stopped thinking about it. And now, with more perspective, I want to try and articulate what it is about these particular kinds of filters in this very particular circumstance that bothered me so much.

Digital cameras are, themselves, a filter—each one reflects the technology and aesthetics of its time. A photo taken on an early 2000s digital camera, for instance, captures not only the subject but also the era's unique imperfections—grainy textures, soft focus, lower resolutions, and muted colors. These qualities are part of the photo’s authenticity, a snapshot of history shaped by the camera’s limitations.

Adding filters that emulate an old type of film erases that context, replacing the original look with a trendy (at the time), artificial aesthetic that distorts the photograph's integrity. To me, that defied what I thought the purpose of the job was, which was to document these factories in that particular moment in time.

Photography, at its core, is meant to document reality, right?

(In this particular context. There is a ton of nuance to this and it depends on the final application. Art and fictional storytelling is obviously exempt from this.)

When we impose nostalgic type filters after the fact, we lose the beauty in the imperfections that make each image a product of its time. The quirks of an older camera aren’t flaws to fix, but historical markers, telling the story of how photography has evolved.

By leaving photos unfiltered, we preserve their original essence, celebrating the authenticity of the medium. Rather than seeking a nostalgic effect through modern editing tools, we should appreciate the unique aesthetic each camera offers, embracing the imperfections as a reminder of the evolving art of photography.

It took a little while, but that trend went away and now almost everyone avoids those filters. GE obviously changed their approach to how they present photographs on their Instagram.

In retrospect, those photo filters were an indication of that era, a mix of old and new. In a way, we can look back on this era with nostalgia on top of nostalgia.

Wait.

Are the photos with the filters more interesting than the original photos I made with just my camera?

Ohh. I get it now.

ARE YOU SUBSCRIBED?

If not, hit that button below. This newsletter comes out once a week. The main stories will always be free but you can pay and if you send me your mailing address I will send you something special in the mail.

You can also support this newsletter by hitting the “like” button or sharing it with a friend.

Thank you.

Zach Vitale has a non-destructive workflow and a self-destructive attitude.

Kristen Neufeld is busy deleting all her photos with old timey filters from her Instagram.

For my tastes, the crops do more to enhance than the filters. But I’ve never cared for filters much.

halfway through I was about to message/respond/ whatever and tell you that the filters were the thing you wanted from the camera in terms of a marker of an era, and then you arrived there yourself, so I didn't have to message - but I wanted it to be known that I thought that and the world is meaningless, so, nice post